Two men, one an heir and the other an unscrupulous financier, were responsible for Washington losing its two American League baseball teams, 11 years apart.

The first was Calvin Griffith. He did what his uncle, Clark Griffith, never considered: moving the original Washington A.L. team to Minnesota. The District then was stuck with an expansion team doomed to failure, finishing no better than eighth out of 10 teams for six straight seasons. Once the predatory Robert E. Short bought the team with borrowed money on a shoe-string after the 1968 season, he spent three years bad-mouthing D.C. baseball fans and RFK Stadium, where the team played. Then he took the expansion bunch to Texas.

Before Clark Griffith came on the scene in 1912 as manager and part-owner, the viability of a major league team in Washington was being called into question. Attendance was disappointing, but that likely was a function of the ineptitude of the team’s players. Thanks to the presence of Walter Johnson and a much improved cast of character Griffith assembled, Washington jumped to second place in each of the first two seasons he managed.

A slump in attendance as World War I raged in Europe and as the team under-performed renewed talk of D.C. being unable to support a major league team, but Griffith’s penchant for positive promotion quieted those murmurs and bought time for him to become the principal owner. He soon assembled a team that would win consecutive A.L. pennants during the prime of Babe Ruth. He spent money improving the stadium that came to bear his name, boosting attendance and fielding competitive teams from 1924 through 1933, his last pennant-winning squad.

Griffith was never really a wealthy man and had no source of income other than the team and stadium he owned. Meanwhile, men worth millions became the owners of most other major league teams. Griffith was slow to adapt to the emergence of the farm system. Although he unexpectedly had two second-place finishes during World War II, the Nationals (more often referred to as the Senators) would never compete for a pennant after that in his lifetime.

For 1955 through 1959, the Senators were horrible. Attendance tanked. The stadium not only had the smallest capacity in the league, it had become outdated, with little adjacent parking and fewer people using the streetcar line that stopped there. (Washington’s subway was years away.) The surrounding neighborhood was deteriorating.

Even though Congress, which controlled D.C. government, eventually approved construction of a new stadium, several years after Clark Griffith died in October 1955, his nephew and informally adopted son Calvin Griffith had his sights on greener pastures. Although he spoke on the record about his commitment to D.C., Calvin was negotiating with officials in Los Angeles to move the team there.

The owners of the Dodgers and Giants beat him to the punch. But after 1959 season, ostensibly dissatisfied with the new D.C. stadium’s location, the younger Griffith announced plans to move the team to the twin cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul in Minnesota. Only because he couldn’t get the backing of enough fellow owners was his plan temporarily foiled.

The 1960 Senators were a team with potential. The roster included two future Hall of Famers, the league’s best lefty pitcher, a future MVP at short and a future all-star catcher. A late season slump kept the Nats from finishing with a winning record, but the outlook was bright. It would not be in Washington, however. In simultaneous moves, American League owners OK’d Calvin Griffith’s desire to move the original Senators franchise to Minnesota while awarding D.C. an expansion team, which inexplicably kept the name “Senators.”

For a few years, both Twins and the expansion team claimed the records of the original Washington A.L. franchise. With a core of players who reached the majors in Washington, the Twins won the A.L. pennant in 1965.

After the original local ownership group of the expansion team sold their shares in 1963 to D.C. minority partners James M. Johnston and James H. Lemon, it looked like the team was in stable hands. But Johnston died late in 1967, and Lemon did not have the money to continue on his own. He had to put the team up for sale. Two D.C.-based groups of investors bid to buy the team. So did groups that included Bob Hope and another with Bill Veeck, all promising to keep the team in Washington. Somehow, they were outbid by Short.

Financial records later revealed that Short put up just a few thousand dollars of his own money to buy the Senators. The rest of the purchase price came from loans.

A fund-raiser for the Democratic party, Short’s business base was in Minnesota. He had acquired at a bargain price pro basketball’s Lakers before selling the team for a huge profit and allowing the team to abandon Minneapolis for Los Angeles.

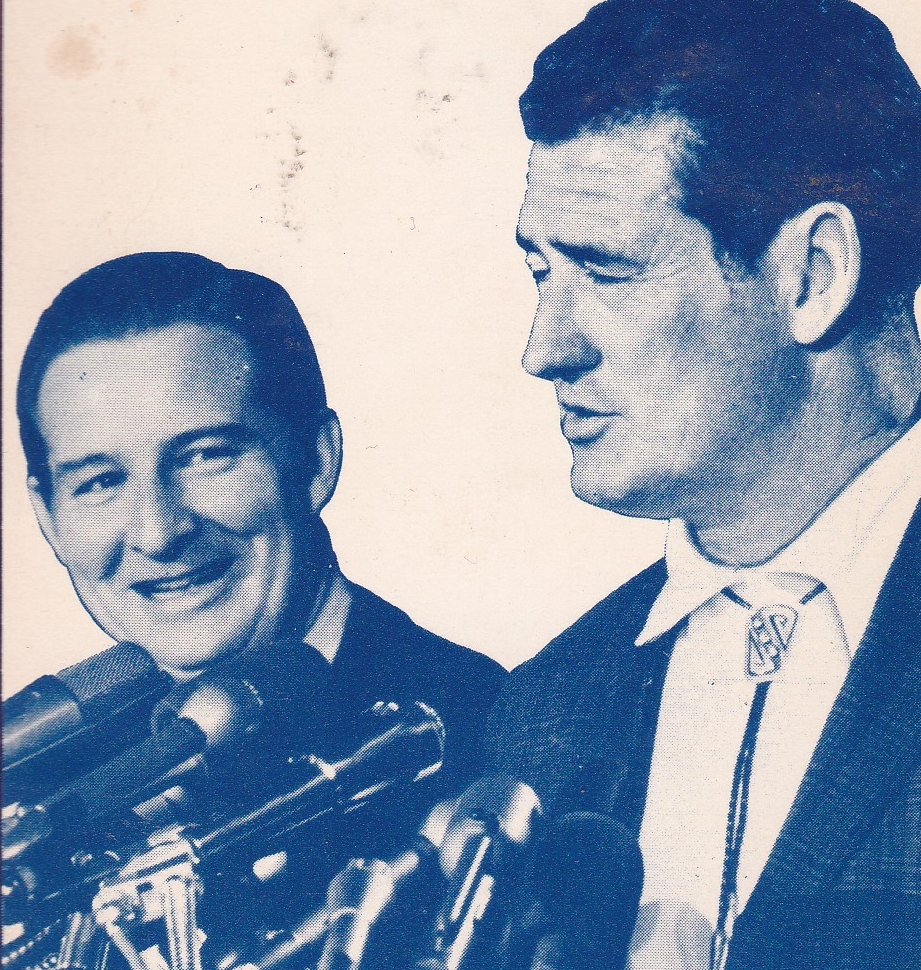

When the deal closed in January 1969, Short immediately fired longtime Senators’ general manager George Selkirk and decided to take on that role himself. He did manage to surprise the baseball world by persuading Ted Williams to manage the Senators. With essentially the same roster as 1968, Williams helped several of his players, most notably slugger Frank Howard and weak-hitting shortstop Ed Brinkman, have career seasons. Washington finished 10 games over .500 and Williams was voted manager of the year.

Despite a doubling of ticket prices, D.C. attendance rose to just under a million (the second highest in the history of either Washington franchise). That wasn’t good enough for Short, who insisted at one point that a girls’ softball team should be able to draw as many fans as the Senators had drawn.

Sadly, after the 1970 team lost its last 14 games, Short managed to trade away Brinkman and third baseman Aurelio Rodriquez along with pitchers Joe Coleman and Jim Hannan for the over-the-hill Denny McLain and a couple of lesser players.

It’s been suggested that this appalling trade, which Williams opposed, took place so Short could win the vote of the Tigers’ owner, if the Senators were to relocate.

Before talk of a move became more than a threat, Short continued to gut the roster by trading slugging first baseman Mike Epstein and star closer Darold Knowles. All the while he was negotiating with officials in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where he had belatedly scheduled two exhibition games at the end of spring training in 1971, to move the Senators there.

The move was announced before the end of the ’71 season. The Senators famously had to forfeit their last home game when angry fans stormed the field with two out in the bottom of the ninth.

For 33 years, Washington was the largest metropolitan area without a major league team. Many former Senators fan switched their allegiance to the Orioles, 30-plus miles away. Others gave up on baseball. Still others persisted in efforts to get another team for Washington. As happy as they were when MLB voted to move the struggling Expos here for the 2005 season, they surely knew that Montreal fans were feeling what the D.C. faithful had gone through in 1960 and 1971.

So in 1972, what was left of the Senators became the Texas Rangers, who proceeded to finish last in the A.L. West, losing 100 games.